Addressing the Iron Giant (1999) in the Room

For a movie marketed towards children, it sure had a lot to say about the worst parts of American culture

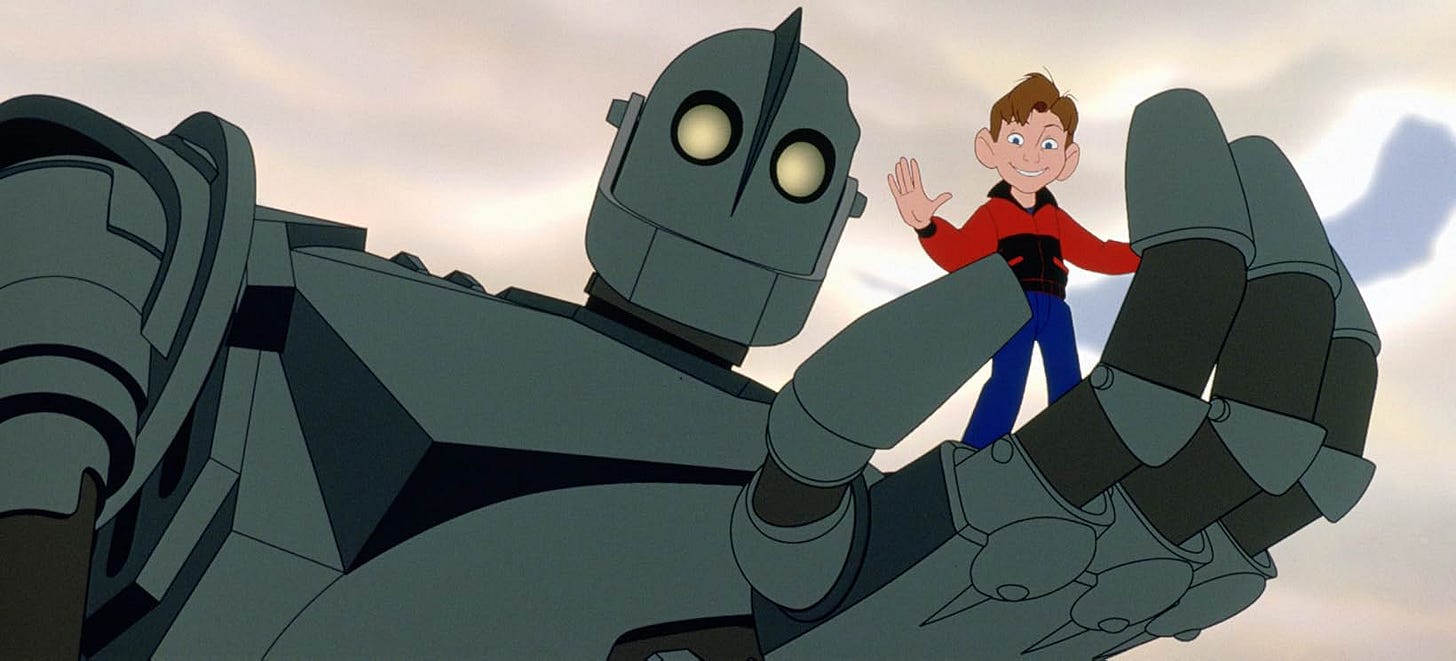

The Iron Giant that I remember watching was silly and sweet. I watched it on VHS at home, sitting on this hefty rocking chair and sinking into the worn out spring cushion. I would pretend that the chair was the giant, as it felt giant to me at the time. From my five year old perspective, the movie was about becoming friends with a giant machine who would swing you around in its hand like a spaceship. An amazing plot, frankly. I watched it again recently, in honor of the film’s 25th anniversary, and while that sentiment is still true, I mostly came to the realization that the film is incredibly badass. On the surface, The Iron Giant, adapted from the 1968 novel The Iron Man, is about a friendship between a boy named Hogarth and a giant robot from space. Upon rewatch, the film actually confronts some of America’s worst characteristics - the military-industrial complex and increasing gun violence. Unfortunately and depressingly, these themes are still as relevant as ever, if not more so, but Hollywood is even less willing to put out any strong political messages. I can’t think of any comparable movies even in the last few years that had any clear messages about American culture. It’s crazy to think this movie had all this going on, 25 years ago and marketed towards children.

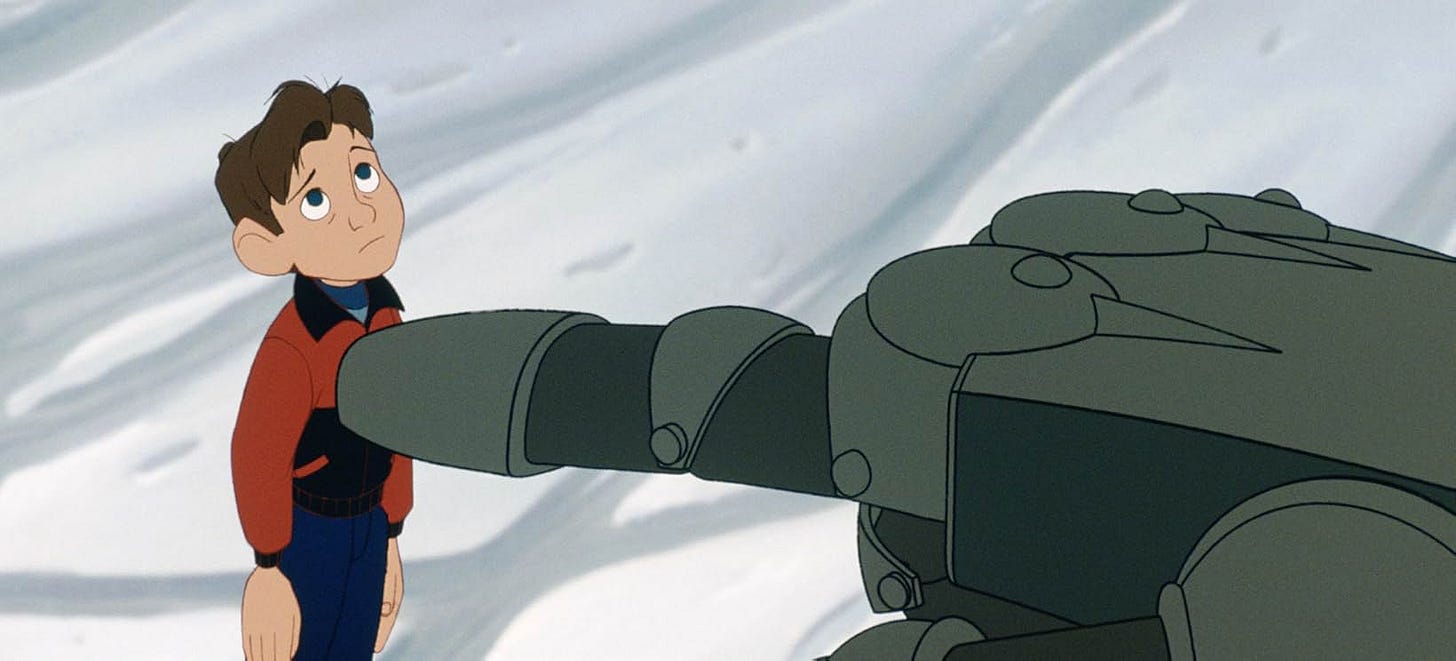

The Iron Giant is violent and dark. Hogarth’s first meeting with the iron giant starts out innocently enough as the iron giant curiously feeds on a power plant, only to be electrocuted for what feels like way too long. Hogarth successfully shuts the powerplant down but the violence is palpable and the sound of the electrocution is visceral. The very real threat of death is so close, but the movie is clear to make a distinction between death at the hands of someone’s violence and the act of dying itself. After the giant witnesses the death of a deer at the hands of hunters and their guns, the giant becomes depressed. Hogarth, in an incredibly wise and moving speech for a child, explains to the giant that it is bad to kill, but it is not bad to die. It is a message that seems obvious, but in light of America’s continual disregard for the violence in this country and perpetuation of violence abroad, it is probably a message that needs to be repeated more often.

Shortly after the deer incident, Hogarth says, “Guns kill,” when explaining to the giant what guns are. This happens in the 53rd minute of the movie to be exact. In the face of growing gun violence and mass shootings, this country is still unable to move on past the public discourse, and therefore has very little progress to show for it. This movie was released in the summer of 1999, only a few months after Columbine, a painful reminder that America’s issue with mass shootings started over two decades ago now and has only gotten worse since. Brad Bird, the director, was also personally dealing with the death of his sister due to domestic gun violence during the production of the film1. The gun violence in this country is a self-inflicted wound, but with the unbelievable controversy that still surrounds the topic, it is refreshing to hear those words - guns kill - stated so directly, and in a children’s film no less.

In the 90s, America had come out on top after the Cold War. Most of the world welcomed the growing influence of the West, led by America. Domestically, the dot-com bubble pushed America’s economy to new heights and brought relative stability to the country. However, this security concealed the violence that it took to remain a superpower as America often turned to the military, whether overtly or covertly, to maintain its influence abroad. Coming out at the tail end of the Disney Renaissance, The Iron Giant had the odds stacked against it. Disney had pumped out hit after hit, with iconic songs and stories that would stand the test of time, and audiences loved it. These movies (The Lion King, The Little Mermaid, Mulan, etc.) had important lessons - overcoming loss, breaking boundaries, courage - but these were stories about going against an individual evil and they were rarely set in contemporary America. Bird, in his directorial debut, set out against the Disney machine without any musical numbers or cute merchandisable side characters, and instead made a movie about the collective and institutional evils that eat at America’s soul.

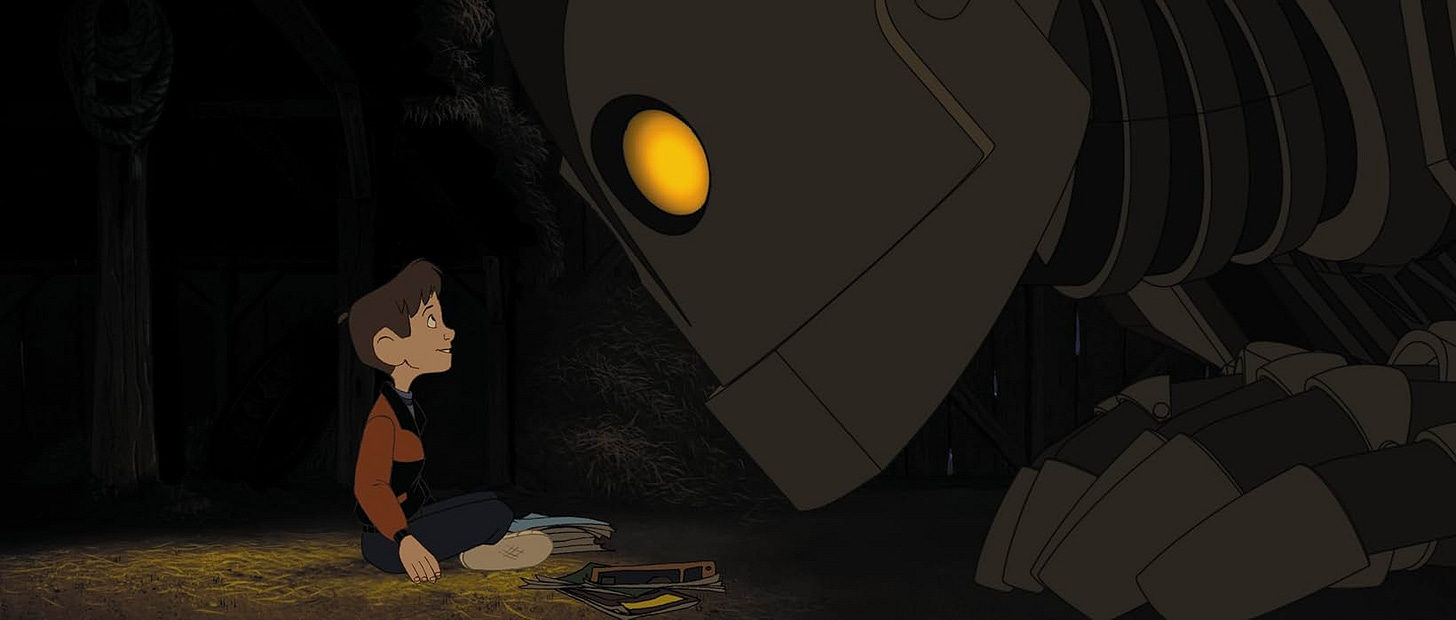

The film does not waste any time before getting to these core messages. Even the titular iron giant has very little backstory. The movie starts with the iron giant crashing down from space and landing off the coast of 1950s Maine. Where did the giant come from? Why did it come to Earth? What caused it to crash? Not important! The giant is never even given a name. The iron giant does not need to be anything else than what it is, an unknown foreign creature that is seen as a threat to a quiet, isolated American town. It is a literal and figurative metaphor for the Cold War anxieties of the time and current anxieties of today.

Hogarth, the main child protagonist, is also not given extensive backstory. He is your everyday 1950s latch-key kid raised by a single mother (voiced by Jennifer Aniston) who loves staying up late watching scary movies and playing with toy guns. What happened to his father? Who cares! Make no mistake, this is a movie with a deep message about our relationship to the unknown, the propensity of violence towards the outsider, and America’s relationship to the military-industrial complex, but we do not need to overcomplicate the characters to get there.

Now enter the main antagonist, Kent, a government employee with an ambiguous job title hellbent on taking the iron giant down. He is an evil guy, drawn with a sharp chin and an intense threatening smile, trying to climb the government ladder to bureaucratic heaven. What exactly does he do in the government? Irrelevant! There is no time to humanize his evil intentions. In the final act, Kent’s blind desire for a promotion essentially dooms the entire town, including himself and even the military, to nuclear oblivion when he launches a rocket targeting the giant only for the giant to be standing right in the center of town. Everyone in town, including Hogarth and his mother, stand calmly, holding each other as they await their fate. Set at the start of the Cold War, this movie is steeped in nuclear anxieties, a time when the argument for a bigger military coincided with the massive economic development in America. The military is not explicitly villainized for launching the missile as it was Kent who lied to the military commanders about the nature of the giant, who then decided to attack in response. However, what do people gain from a military that is meant to protect them, but is instead always looking for a fight that ultimately destroys them and itself? The instinct towards violence and revenge against anything deemed a threat, whether real or not, will always have collateral damage, and this time it was every character in the frame.

To lighten up the film (this is a kid’s film after all) there are characters like Dean. If there was ever anyone who looked like a poster child for McCarthyism, Dean is it - a likable beatnik artist living on the edges of society making abstract art out of scraps, complete with dark hair and tiny goatee. He is not loud or confident. He has no special powers. He doesn’t give long monologues about virtue or honor. He doesn’t do much in the film other than befriend and care for Hogarth and the community around him. When Dean and Hogarth meet for the first time, Dean describes himself with a question: am I a junkman who sells art or an artist who sells junk? Dean is amazing. His line went over my head as a child but stuck with me as an adult. Perhaps this is a reflection from the makers of the film. For those in the movie industry, are you a profiteer selling art or are you an artist selling for profits? I guess this could apply to anyone with a job. How does what we do reflect who we are? In the end, the movie does not overcomplicate the question, it does not matter what you are on the outside - giant robot, junkman, kid, single mom - all that matters is that you are good. Hogarth expresses to the iron giant that all good things have a soul. So then what is good? Another question that can easily spiral into controversy, but The Iron Giant makes it clear, friendship, family, protecting each other, kindness towards strangers, and perhaps most obviously not killing, are all good things.

For all the depictions of gun violence and militarism, this is ultimately a movie about the soul. Hogarth explains that all good things have a soul, therefore the iron giant has a soul because the iron giant is good. It does not matter if the iron giant is human or not. Kent, on the other hand, is human but does not have a soul because he is not good. What good is it to be human if you are not good? The deep friendship that blossoms between Hogarth and the iron giant culminates in Hogarth shouting “I love you” to the iron giant before the giant sacrifices itself to save the townspeople from the nuclear missile. The “show don’t tell” nature of films usually means love is shown with a look or with an action, but here the words are said out loud and it moved me to tears as an adult to hear them. In a film that is also about death, there is no shortage of love nor is the importance of love diminished. Love is good. Those that are good, have souls. Thus those with souls have the capacity to love and love well.

After Hogarth’s declaration of love, the iron giant flies off into space to collide with the missile and save the town. Again, this is a kid's movie, so after almost killing everyone on screen and killing the iron giant, you don’t want to traumatize the kids completely. The iron giant doesn’t actually die in the end. His pieces are scattered all over Iceland, but he slowly builds himself back together, likely to reunite with Hogarth again. Hogarth also mentions that souls never die, and indeed there is something beautiful in regeneration, in being unable to destroy something that is good in nature. Those that are good will always return to us somehow.

Animated movies marketed towards kids are never just for kids. I love how they can give us something otherworldly in ways that live action can’t, telling stories like what if toys were alive? What if a fish got lost? What if feelings were physical beings inside your head? They are artistic representations of life lessons that teach us to dream of a better way to live. Although recent animated hits like Encanto and Turning Red come from underrepresented creators and bring desperately needed diverse viewpoints about family and cultural burdens, their messages mostly encourage viewers to look inward and make individual changes in the face of those burdens, rather than call out the structural and societal ills that are causing them. Those messages also feel muted when buried behind addictive songs and talking animals, as if the studios are only willing to share traditionally underrepresented stories if they can also make them universally appealing. Ultimately, it just feels like a waste of creative potential.

Bird has always been excellent at creating realities that mirror our own, and placing the fictional and fantastical elements into that world without losing the realism. Bird did eventually move to Disney, directing some of Pixar’s biggest hits. Ratatouille puts a rat in the kitchen, but the rats and the humans don’t magically understand each other in this world. The rats are still rats and treated as such and the humans are still humans who despise rats. The Incredibles puts superheroes in 9-5 jobs, along with all the bills and family obligations. I would still consider The Iron Giant one of his best films though, albeit darker. I guess I can understand why the movie flopped at the box office. Audiences probably expected a film about the adventures between a boy and an iron giant, only to get a soul-searching somber meditation on American culture.

Luckily, the movie has rightly become a cult classic. I went into this rewatch thinking it would bring about all this warm nostalgia, that I would be taken back to that giant recliner in my old living room. I would be reminded of the simple friendship between Hogarth and the iron giant, and how much I laughed at the iron giant’s dog-like personality. I thought I would be reminded of the pre-internet days. Kids just can’t run into aliens and hide them like they used to. Instead, I found myself nostalgic for something totally different, for a movie that spoke plainly about its perspective, even political ones, without causing a storm of online discourse. This movie is about becoming friends with a giant robot, but it is also a movie about gun violence, American militarism, and souls - and it rocks! If there was a time to address the elephant(s) in the room, of the bad in our country and culture, it might as well be now.

1 The Iron Giant: Signature Edition (The Giant's Dream) (Blu-ray). Burbank, California, United States: Warner Bros. Home Entertainment. 2016.